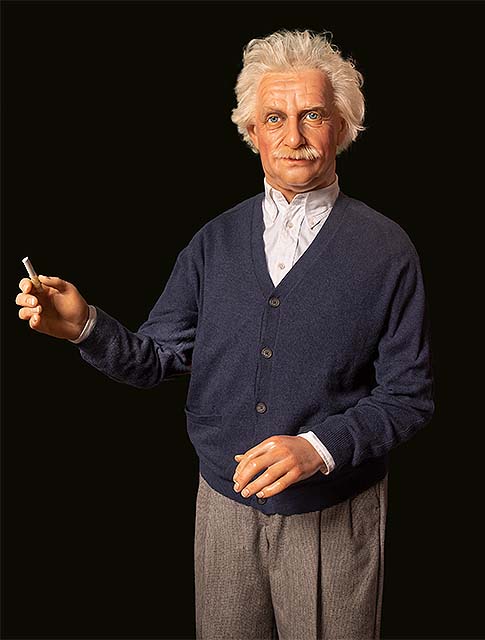

Biography of Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein was destined to be one of the greatest minds in history from a young age. Born in Ulm, Württemberg, Germany, Einstein’s childhood in Munich and early education in Switzerland profoundly shaped his intellectual curiosity about the universe and its functions, defining what would become the rest of his life and career. Widely celebrated as one of the greatest physicists, Einstein is known for his theories of relativity and contributions to quantum mechanics and unified field theory.

After emigrating to the United States in 1933 to escape the ever-growing threat of Nazi Germany, Einstein continued his academic pursuits at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he’d spend the remainder of his years. During World War II, in which his mass-energy equivalence equation (E=mc2) provided the framework for the creation of the atomic bomb, Einstein solidified his legacy as a global humanitarian, advocating for better nuclear control, environmental conservation, and civil rights in America as a longtime pacifist.

Albert Einstein died on April 18, 1955, at the age of 76, in Princeton, New Jersey. He is remembered for being the most influential physicist of the 20th century, revolutionizing modern science as we know it today. Most known for his 1905 papers, which introduced his theories on the photoelectric effect (which won him a Nobel Prize in 1921), Brownian motion, special relativity, and the mass-energy equivalence equation (E = mc2), Einstein saw international fame through his groundbreaking discoveries. With a legacy cemented among the likes of Isaac Newton and Galileo Galilei, Einstein’s theories continue to provide inspiration for countless young scholars across the globe, with centuries of great scientific discovery built on his work to come.

Early Years of Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein was born on March 14, 1879, in Ulm, Württemberg, Germany, as the oldest of two children to parents Hermann Einstein and Pauline Koch. Raised in a secular middle-class Jewish household in Munich, Einstein’s family saw decent success through his father’s business as a salesman and engineer. Hermann, in Albert’s youth, founded Elektrotechnische Fabrik J. Einstein & Cie with his brother, a company focused on the mass production of electrical equipment. Pauline, Albert’s mother, ran the family household and watched over the Einstein children, including Albert’s younger sister, Maria, who went by the name Maja.

DID YOU KNOW?

Einstein was raised in a secular middle-class Jewish household in Munich.

An inquisitive young man, Einstein attended elementary school at the Luitpold Gymnasium in Munich. His years spent at the institution were not fond ones – in fact, he often found the rigid curriculum to be extremely alienating and stifling, failing to foster the environment of creativity and originality he longed for. At age 12, Einstein fell deep into religious beliefs, choosing to spend his free time composing songs in praise of God. Although his opinions on religion would begin to change as he dove deeper into contradictory science books, his love for classical music would remain until his passing, including a passion for playing the violin.

One of the most important influences on Albert Einstein’s early years came in the late 1880s with a young medical student, Max Talmud. Known for his frequent dining at the Einstein estate, Talmud quickly became an informal tutor to Einstein, introducing him to the ideas of higher philosophy and mathematics. Talmud and Einstein, in their studies, read a children’s science series by Aaron Bernstein, Naturwissenschaftliche Volksbücher (1867-68; Popular Books on Physical Science), in which Bernstein imagined riding alongside electricity. What started as a theoretical idea quickly became Einstein’s first pivotal inquiry, that is, a determination to discover what a light beam truly looks like. Around this time, he also wrote his first scientific paper, “The Investigation of the State of Aether in Magnetic Fields.”

Unfortunately, around the time Einstein was 15, his father’s success in business began to decline. In 1894, Hermann was forced to move to Milan, Italy, to work alongside a relative after his company failed to secure an important contract to supply electricity to the city of Munich, leaving Einstein behind in a boardinghouse to complete his education. Leading a lonely and miserable life with the threat of mandatory military service upon his 16th birthday looming over his head, it only took Einstein six months before he ran away from Munich to reunite with his parents. Now a dropout and a draft dodger, his future was looking more uncertain and dire than ever.

Ever the scholar, Albert Einstein found he could apply directly to the Eidgenössische Polytechnische Schule (or the “Swiss Federal Polytechnic School”) in Zürich without a high school diploma if he was able to pass their rigorous entrance examinations. While he had previously earned high marks in mathematics and physics, Einstein struggled with chemistry, biology, and French, and was told he could only attend the polytechnic school under the condition that he complete his formal education first. This led him to a special high school in Aarau, Switzerland, run by Jost Winteler, which he graduated from in 1896. At the same time, Einstein decided to renounce his German citizenship, remaining stateless until after he completed his studies at the polytechnic school in Zürich in 1900, when he was granted Swiss citizenship in 1901.

Personal Life of Albert Einstein

During his time in Zürich, Albert Einstein boarded with the Winteler family, with whom he’d become lifelong friends. Winteler’s daughter, Marie, was known to be Einstein’s first love, while Winteler’s son, Paul, would go on to marry Maja, Einstein’s sister. Despite the love he had for Marie, the two never married. Fondly referring to his time in Zürich as the best years of his life, Einstein made many notable friends while studying at the Eidgenössische Polytechnische Schule, such as Marcel Grossmann, a mathematician, and his future wife, Mileva Marić, a physics student from Serbia.

After graduation in 1900, Einstein’s relationship with Marić began to deepen, much to his parents’ displeasure. They opposed her Serbian background, especially since Marić’s family was Eastern Orthodox Christian. This didn’t stop the young couple from being together, however, and in January 1902, they welcomed a daughter, Lieserl, into the world. While her fate is unknown, it is most commonly believed that she was either given up for adoption or died of scarlet fever. Despite having a child together, Einstein could not marry Marić without a job to support their family, and his father’s business went bankrupt. Thrust into an extremely low period of his life, Einstein desperately took on lowly tutoring jobs, but was ultimately fired from these roles.

It wasn’t until late 1902 that Albert Einstein was able to secure a solid job, all thanks to the father of his lifelong friend, Marcel Grossmann, who recommended him for a clerk position in the Swiss Patent Office in Bern. This newfound stability gave Einstein the confidence he needed to officially marry Marić, doing so on January 6, 1903. Right before their marriage, Einstein’s father had grown increasingly ill, giving Einstein his blessing to marry Marić right before his passing. Einstein would spend years agonizing over his father’s death, believing he had failed due to his lack of success in his youth. In the coming years, Einstein and Marić would welcome sons Hans Albert (1904) and Eduard (1910) in Bern.

Not only was the clerk position a great turning point for Einstein financially, but it also allowed him ample time to pursue his scientific inquiries, laying the groundwork for his future breakthroughs. In 1905, often referred to as Einstein’s “miracle year,” he published four papers in the Annalen der Physik, each of which would go on to alter the course of physics forever.

DID YOU KNOW?

Einstein published four papers in the Annalen der Physik, each of which would go on to alter the course of physics forever.

The first, “Über einen die Erzeugung und Verwandlung des Lichtes betreffenden heuristischen Gesichtspunkt” (or “On a Heuristic Viewpoint Concerning the Production and Transformation of Light”), explained the photoelectric effect by applying the quantum theory to light. He wrote that if light occurs in tiny photons, then they should be able to precisely knock out electrons in a metal. The second, “Über die von der molekularkinetischen Theorie der Wärme geforderte Bewegung von in ruhenden Flüssigkeiten suspendierten Teilchen” (or, “On the Movement of Small Particles Suspended in Stationary Liquids Required by the Molecular-Kinetic Theory of Heat”), offered the first proof of the existence of atoms by analyzing Brownian motion, or the motion of tiny particles suspended in still water, to calculate the size of the atoms and Avogadro’s number. The third, “Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper” (or “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies”), laid out the theory of special relativity, based on Einstein’s earlier principle of relativity formulated in his polytechnic school days: the speed of light will remain constant no matter how fast one moves. The fourth and final, “Ist die Trägheit eines Körpers von seinem Energieinhalt abhängig?” (or “Does the Inertia of a Body Depend Upon Its Energy Content?”), showed how relativity theory led to the mass-energy equivalence equation (E = mc2), which provided a basis for many important discoveries in modern science and mathematics.

While other scientists, such as Henri Poincaré and Hendrik Lorentz, had already begun discussing the theory of special relativity, Albert Einstein was credited as the first scientist to put the whole theory together and recognize it as a universal law of nature. He alone came to the realization that the two pillars of 19th-century physics, Newton’s laws of motion and Maxwell’s theory of light, were in direct contradiction, allowing him to make his own groundbreaking scientific discoveries. While some speculate that Marić was a cofounder of this theory, finding references to special relativity as “our theory” in private letters between the couple, Marić had already abandoned physics after failing her graduate exams twice, and there is no official record of her involvement.

At first, Einstein’s papers were widely ignored by the scientific community. However, this began to quickly change after his theories caught the attention of the most influential physicist of his generation, Max Planck, the founder of quantum theory. Thanks to this high recognition, Einstein began to rapidly rise to fame in the academic world, receiving invitations to lecture at international meetings, such as the Solvay Conferences. He also saw many offers to teach at extremely prestigious institutions, such as the University of Zürich, the University of Prague, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, and finally the University of Berlin, in which he served as director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics from 1913 to 1933.

Despite his rising fame and newfound academic successes, Albert Einstein’s marriage was anything but great – in fact, it was quickly falling apart. Constantly on the road and lost in his studies, Einstein failed to balance family and career, frequently arguing with Marić about their children and horrible finances. Knowing that his marriage was doomed, considering their 1914 separation, Einstein found comfort in his cousin, Elsa Löwenthal, with whom he had an affair and later married in 1919 after finally divorcing Marić. In his divorce, Einstein agreed to give Marić any money he might receive from winning a future Nobel Prize.

Interesting Facts About Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein wrote of two “wonders” that shaped his youth – his first encounter with a compass at age five, which fueled his lifelong interest in invisible forces, and his discovery of geometry at age 12, learning from a book he deemed his “sacred little geometry book”.

Einstein struggled with speech challenges in his early years.

Albert Einstein co-founded the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in July 1918 with Chaim Weizmann. It is the second-oldest institution of higher learning in Israel and was founded 30 years before the establishment of the State of Israel.

In 1930, during a trip to California, Einstein appeared alongside Charlie Chaplin, a famous comic actor, during the Hollywood debut of the film City Lights.

In 1933, the International Rescue Committee (IRC) was organized at the request of Albert Einstein to assist German victims and enemies of the rising Nazi party.

Einstein didn’t believe in a personal God, but rather, believed that there was an “old one” who was the ultimate lawgiver, turning to the God of the 17th-century Dutch-Jewish philosopher, Benedict de Spinoza, who was a God of harmony and beauty.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) director, J. Edgar Hoover, tried to recommend that Albert Einstein be kept out of America through the Alien Exclusion Act during World War II, but was overruled by the U.S. State Department.

During World War II, Einstein sought to help war efforts by auctioning off personal manuscripts, selling a handwritten copy of his 1905 paper on special relativity for $6.5 million. It currently resides in the Library of Congress.

In 1952, Albert Einstein was offered the post of president of Israel by its premier, David Ben-Gurion. He respectfully declined, as he was a prominent figure in the Zionist movement.

Einstein reportedly hated wearing socks and would outright refuse to wear them.

Although he never took an IQ test, it is thought by many that Albert Einstein’s IQ was around 160, which is commonly considered on the genius level.

What Albert Einstein is Most Known For

Albert Einstein’s 1905 papers on the photoelectric effect, the discovery of atoms, special relativity theory, and the mass-energy equivalence equation (E=mc2) were just the start of his great contributions to modern physics. In fact, his 1905 theory on special relativity led to a decade of deep struggle and thought – Einstein had made a crucial flaw by not previously considering its applications to gravitation or acceleration. In November 1915, Einstein was finally able to complete his general theory of relativity, which he considered to be his greatest masterpiece, describing gravity as the curvature of space-time.

DID YOU KNOW?

In November 1915, Einstein finally completed his general theory of relativity, his greatest masterpiece.

Unfortunately for Einstein, he had previously given six two-hour lectures at the University of Göttingen that explained an incomplete version of his general relativity theory, missing key mathematical details that would be present in his final November 1915 publication. Mathematician David Hilbert, who had helped organize the lectures at the university, took this incomplete version and filled in its missing details, submitting a paper on general relativity only five days before Einstein published his own, making it appear as if Hilbert had come up with the theory himself. The pair would later reconcile over their differences and retain their friendship, but physicists now refer to the action from which the equations were derived as the “Einstein-Hilbert action,” although the theory itself is solely attributed to Einstein.

At the same time that Albert Einstein was wrapping up his general relativity theory, World War I broke out, causing global devastation and putting a halt to his work. As a lifelong pacifist and avid defender of civil and humanitarian rights, Einstein was one of four intellectuals in Germany to openly sign a manifesto opposing Germany’s entry into the war. He called nationalism “the measles of mankind,” and was extremely disgusted by the terrors unfolding across the world. In post-war chaos, radical students seized control of the University of Berlin in November 1918, holding the rector of the college and many professors hostage. Einstein, a well-respected member of the community, alongside Max Born, another German physicist, quickly stepped up to mediate the crisis, fearing police intervention would result in a tragic confrontation. Together, they were able to broker a compromise between the students and faculty that resolved the tensions, a highlight of Einstein’s great depth for peace.

After the war, Einstein’s studies resumed, leading to two expeditions (one on the island of Principe, off the West African coast, and the other on Sobral in northern Brazil) to test his prediction of deflected starlight near the sun by observing the May 29, 1919, solar eclipse. On November 6 of the same year, the results of both expeditions were presented in London at a joint meeting of the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society. It was these expeditions that truly began to blow Einstein into the world-renowned physicist he is known as, with many beginning to refer to him as the successor to Isaac Newton, one of the greatest physicists in history, and the leading figure of the 17th-century Scientific Revolution.

In 1921, Albert Einstein embarked on his first of several world tours, traveling to the United States, England, Japan, and France to speak on his discoveries and theories, amassing crowds of thousands of people everywhere he went. As he traveled from Japan, Einstein learned that he had received the Nobel Prize for Physics for his work on the photoelectric effect. During his acceptance speech, however, Einstein shocked the crowd by speaking on his theories of relativity instead of the photoelectric effect, for which he had received the Nobel Prize.

In the following years, Einstein launched the new science of cosmology, which pulls together astronomy and physics to understand the physical universe as a whole. He predicted that the universe is dynamic, constantly expanding or contracting, which went against the held belief at the time that the universe was a static thing. Despite his beliefs in a dynamic universe, Einstein reluctantly introduced the cosmological constant as a way to stabilize his model of the universe; however, he would later declare this to be his “greatest blunder” after meeting with astronomer Edwin Hubble in 1930, who had discovered the universe was indeed expanding in 1929 and, therefore, confirmed Einstein’s earlier thoughts.

In the wake of his fame and success, Albert Einstein was finally faced with the inevitability of backlash and threat. With the rise of the Nazi movement in Germany, theories of relativity were branded as “Jewish physics,” with the Nazi party calling for the denunciation of Einstein and his theories through sponsored conferences and book burnings. In 1931, One Hundred Authors Against Einstein was published, with physicists including Nobel laureates Philipp Lenard and Johannes Stark denouncing relativity. Around the same time, a Nazi organization published a magazine with the caption “Not Yet Hanged” and a picture of Einstein on the cover. Tensions were so bad that he even had a price on his head. As the threat against his life rose, Einstein decided to leave Germany forever in December 1932, going so far as to deviate from his usual pacifist ways to argue the justification of defense with arms against Nazi aggression. Without so much as a glance back, Einstein moved to the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, New Jersey, which would quickly become a hub for physicists around the world.

World War II: Albert Einstein’s Environmental and Social Initiatives

The 1930s proved to be a hard decade in Albert Einstein’s life. Not only had he recently left Germany under growing Nazi threat, but his son, Eduard, was diagnosed with schizophrenia and suffered a mental breakdown in 1930 that would leave him institutionalized for the rest of his life. Three years later, in 1933, Einstein’s close friend, Paul Ehrenfest, who had helped him develop the general relativity theory, committed suicide, and three years after that, in 1936, his beloved wife, Elsa Löwenthal, passed away.

Drowning in grief, Einstein had little time to mourn before he was faced with a new issue – whether or not his mass-energy equivalence equation (E=mc2) could make an atomic bomb possible. While he himself had considered this possibility in 1920, Einstein had dismissed the thought as a longtime pacifist, environmentalist, and humanitarian. An atomic bomb would completely go against those values. However, between 1938 and 1939, Otto Frisch, Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner, and Fritz Strassmann found that vast amounts of energy could be unleashed by splitting a uranium atom, and the rest was history.

In July 1939, physicist Leo Szilard was able to convince Albert Einstein to send a letter to the U.S. President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, to urge him to develop an atomic bomb. With Einstein’s guidance, the letter was drafted and signed on August 2nd, delivered to Roosevelt by one of his economic advisers, Alexander Sachs, on October 11th, and replied to on October 19th, in which Roosevelt informed Einstein that he had organized the Uranium Committee to discuss the atomic issue.

Granted permanent residency in the United States in 1935 and American citizenship in 1940 (although he still chose to retain his Swiss citizenship), Einstein should have been a great resource in the American creation of the atomic bomb during World War II. While his colleagues were asked to journey to Los Alamos, New Mexico, to develop the first atomic bomb under the Manhattan Project, Einstein was never asked to participate, despite being the man whose equation set the whole process in motion. Fearing his lifelong association with pacifist and socialist organizations, the U.S. government chose to exclude Einstein from atomic pursuits, instead asking him to help the U.S. Navy evaluate designs for future weapons systems.

DID YOU KNOW?

Einstein was granted permanent residency in the United States in 1935 and American citizenship in 1940.

In 1945, while on vacation, Albert Einstein learned that an atomic bomb had been dropped on Japan. Horrified by the news, he quickly joined the growing international efforts to bring the atomic bomb under control, forming the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists. With the physics community split on the idea of the creation of a hydrogen bomb, Einstein joined J. Robert Oppenheimer, the director of the Manhattan Project, to oppose the development of a hydrogen bomb, instead advocating for international controls on the spread of nuclear technology. Ever the pacifist, he also became increasingly interested in anti-war activities and the improvement of civil rights for African-Americans in the United States. In the late 1940s, Einstein became a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), drawing parallels between the unfair treatment of Black people in America and Jewish people in Nazi Germany, whom he had to flee Germany over. Continuing in his advocacy, Einstein also spent years calling for responsible resource management and environmental conservation, remaining an inspiration for modern environmentalists in the pursuit of clean energy technologies and policies.

How Albert Einstein Lived Out the Remainder of His Life

In the later years of his life, Albert Einstein grew increasingly isolated from the physics community, despite his continued discoveries in the theory of general relativity. Pioneering theory on higher dimensions, the possibility of time travel, wormholes, black holes, and the creation of the universe, Einstein was stuck in relativity, while the general physics focus had shifted to quantum theory due to major discoveries into the secrets of atoms and molecules. He was essentially stuck in the “old news” of the physics community, even going so far as to engage in a series of historic private debates with Niels Bohr, creator of the Bohr atomic model, in an attempt to find logical inconsistencies in quantum theory. The most celebrated of Einstein’s attacks on quantum theory came in 1935 with the EPR (Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen) thought experiment. While Einstein concluded that quantum theory violated general relativity theory, it was later found through further experimentation that quantum theory was correct about the EPR experiment, not Einstein in his conclusion.

To further the divide between Einstein and his colleagues, the great physicist had developed an obsession in 1925 with discovering a unified field theory. This theory would be all-embracing and unify the forces of the universe and the laws of physics under one framework. Once he was through with trying to oppose quantum theory, Einstein turned to trying to incorporate it into his unified field theory instead, alongside ideas of light and gravity. Older, stubborn, and very set in his ways, Einstein essentially confined himself to Princeton, rarely traveling beyond long walks around the area with those closest to him. His late days were spent in deep conversation about physics, religion, politics, and the unified field theory. He even published an article on his new theory in Scientific American in 1950, but it is regarded as incomplete because of its failure to address the strong force.

On April 18, 1955, at the age of 76, Albert Einstein passed away from an abdominal aortic aneurysm at the Princeton Hospital in Princeton, New Jersey. He reportedly declined surgery after being admitted to the hospital, content with his life as he had lived it. Upon autopsy of his body, pathologist Thomas Stoltz Harvey removed Einstein’s brain without his family’s consent for preservation and future study. Keeping with his wishes, the rest of his body was cremated, and the remains scattered in a publicly unknown location. In 1999, Canadian scientists studying Einstein’s brain found that his inferior parietal lobe, which is responsible for processing spatial relationships, 3-D visualization, and mathematical thought, was 15% wider than in those with normal levels of intelligence. It is believed this was part of the reason behind his high intelligence. Albert Einstein’s brain can now be found at the Princeton University Medical Center.

FAQs

Why is Albert Einstein famous for the theory of relativity?

Albert Einstein is famous for his theories of relativity, as they fundamentally changed our understanding of space, time, and gravity. While his theory of special relativity found that the speed of light is constant and established the equivalence of mass and energy, his general relativity theory expanded to define gravity not as a force, but as the curvature of space-time created by mass.

What were Albert Einstein’s major contributions to modern physics?

Albert Einstein is most known for his theories of relativity (special and general) and the discovery of the photoelectric effect, the mass-energy equivalence equation (E=mc2), and the existence of the atom. His research spanned from quantum mechanics to invisible forces of nature, such as light, time, gravity, and energy, which radically changed the way we approached science and the universe around us.

How did Albert Einstein impact the development of atomic energy?

Albert Einstein’s discoveries of the photoelectric effect and the mass-energy equivalence equation (E=mc2) laid the groundwork for understanding atomic and nuclear energy, allowing scientists to discover and create atomic bombs. On top of his research, Einstein also encouraged U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to accelerate research into atomic energy, leading to the creation of the Manhattan Project and subsequent nuking of Japan during World War II.

What organizations did Albert Einstein support or help establish?

Albert Einstein co-founded the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in July 1918 with Chaim Weizmann. It is the second-oldest institution of higher learning in Israel and was founded thirty years before the establishment of the State of Israel. He also helped establish the International Rescue Committee (IRC) in 1933, which was organized at the request of Einstein to assist German victims and enemies of the rising Nazi party.

What are some notable inventions and discoveries by Albert Einstein?

While Albert Einstein is most known for his theories of relativity, it was his discovery of the photoelectric effect that won him a Nobel Prize in 1921. He is also known for his mass-energy equivalence equation (E=mc2), his discovery of the atom, and his contributions to quantum mechanics as a whole. Einstein studied unified field theory in the late years of his life, but it was left incomplete upon his death.